The ‘Aalster method’. Which Dutch beekeeper would still use this method today? Yet, some 60 years ago it was the most common beekeeping method in the Netherlands. How did it work?

The origin

This old beekeeping method was invented around 1950 in Aalst in Brabant, just south of Eindhoven, and later refined by the famous Ir. Mommers at the bee research station of ‘De Ambrosiushoeve’ in Hilvarenbeek. It is actually a special form of a two-queen system.

After the Second World War, Dutch beekeepers slowly started working with movable-frame hives, but they were not quite sure how to go about it, as they were used to the methods of beekeeping in skeps with fixed combs. During the transition to movable-frame hives, there was a lot of experimentation going on in the early years. It is very fascinating to read through old volumes of the Dutch beekeeping magazine ‘Groentje’ how things were done in the thirties of the last century. It has all been digitised and is on the internet (bit.do/fSMLQ), in Dutch, of course.

The method

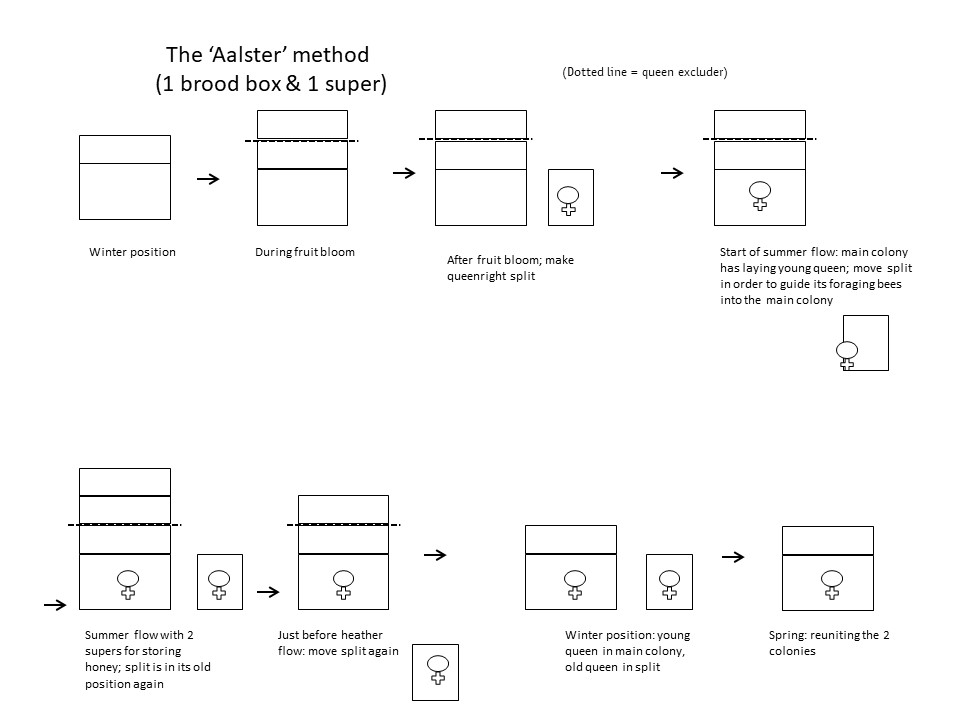

The Aalster method is a swarm prevention method, in which a queenright split is made just before the swarming period, i.e. just after the fruit and rapeseed flowering period. This technique is within reach of everyone who has followed a basic beekeeping course. You do have to find the queen, but that usually works out without too many problems in spring.

We put the split with the old queen right next to the now queenless main colony, for example in a six-frame hive. The aim is to strengthen the main colony several times during the season by using the ever growing split to strengthen the main colony. This is why the split must be placed right next to the main colony. By removing the old queen from the colony before swarming time, we keep the colony from swarming.

What happens when we make a split? The main colony is now going to produce emergency queen cells. On the 13th day we have to break these to prevent afterswarms. In the main colony, after the brood of the old queen has been capped, there is no brood to care for for a while. The emerging young bees are therefore in good shape and soon available for the summer honey crop.

Summer and early autumn

If we allow the queenright split to continue to grow, it will probably swarm soon, because it contains an old queen, which will swarm much sooner than a young one. To prevent this, we let the forager bees of the split fly off at the main colony about six weeks after producing it. By now, the main colony will have bred a young queen. Probably a brood nest has already been formed, if all went well. We move the split a little forward from the row or on top of the main colony. The forager bees from the split now enter the main colony and strengthen it considerably. The weather must be good for this operation, otherwise too few bees will fly.

During the flowering of the heather, the beekeeper can possibly perform the same trick again, or else transfer frames with capped brood from the split to the main colony. In short: the main colony produces the crop, while the split has to regain its strength again and again. However, such splits, if well cared for, can indeed hibernate successfully.

Many beekeepers found that repeated flying off of forager bees from the split to the main colony was just too much of a hassle. They simply provided the splits with more room, but this went at the expense of the main colony. In this way the method lost much of its value, because its essence, the strengthening of the main colony, was lost.

The next spring, just before the flowering of the cherry trees, the main colony and the split were united again and the number of colonies was back to the old level.

Pros and cons

We must bear in mind that the method was very much aimed at a rich summer nectar flow as we used to know it: buckwheat, clover, summer flowers. We don’t have that anymore in many places, unfortunately. The main honey flow has shifted strongly to spring and the method does not really fit well with that. By the way, did you know that spring honey is largely brought in by the end-of-life winter bees?

Furthermore, uniting the main colony and the split in autumn may also be better than in the next spring: you only have to feed one colony instead of two and that saves money and time. Such a colony hibernates stronger and no matter how you look at it, hibernating a colony in a six-frame hive is not the easiest thing to do.

A great advantage of uniting the two parts in spring is that a colony’s queenlessness is actually not such a disaster, because you can easily remedy that through this unification. Yes, even in the past colonies sometimes hibernated poorly and queenlessness or an infertile queen is of all times. In the spring, this unification usually goes quite well by placing a sheet of newspaper between the two colonies.

Of course, sometimes things went wrong. For example, if the young queen did not become fertilised or did not even return to the colony from her nuptial flights. No worry: then the main colony and the split were united again. All in all, it was a method that provided clarity, also for the novice beekeeper.

What was actually the merit of this method? First of all, it was a well-thought-out and clear method, and that helped the novice beekeepers enormously at the time with the switch to mobile-frame beekeeping. But what often happened in practice was that the beekeeper made a split in the spring and considered that he had done enough. As I said, that was just not the idea.

Another frequently heard objection was that the bees raise queens from emergency cells. For a long time this was considered unfavourable: such queens were thought to be inferior. Current insights state that this objection is actually not that important. What matters is that there are enough young worker bees present and pollen to provide the queen larvae with enough royal jelly. The main colony is actually starter and finisher colony in one. In this context I would like to refer to my article ‘2×9=Golz‘, in which the old queen is removed from the colony, which then produces queen cells twice. There is no question of flying off of forager bees or otherwise strengthening the main colony in this method.

Incidentally, all that flying off is rather stressful for main colony and split. It disrupts the harmonious composition of the two colony parts to some extent. And in practice, the transfer of forager bees from the split to the main colony did not always work out well.

Gradually, Dutch beekeepers also became strongly interested in selection. It was the time of the introduction of the carnica bee. If you renew your queens using emergency cells, selection is difficult to achieve unless you introduce a frame with eggs and larvae of a selected colony.